It’s November 17th, 1957. Thats why you hear crying on the street corner. That’s why you see all the mothers in town keeping their children inside. Back in 1939 this was the day that Little Eddie disappeared.

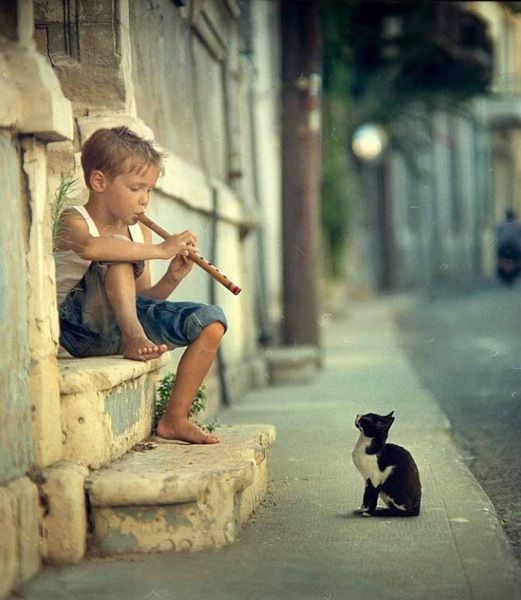

A rough thought of how Eddie might have appeared. But really, imagine him any way you wish.

Little Eddie had only been in town one month. He’d arrived on the cold evening of the 17th of October, while all the trees were turning from green to gold, and from gold to brown. All the trees, that is, except for the one down at the edge of the sliver of water running through town. That one was turning from gold to green. In fact, as I recall, people called it “The Backwards Tree”.

But for the one month that Eddie lived in Brookbrier, it was called “Eddie’s Tree”, because the small boy had practically adopted it from his first night in town. No one knew where Eddie had come from, and no one knew what his age was. Some said five while others said eight. His appearance was poor, and so was his English. He spoke mostly Polish.

Eddie arrived in the middle of the War. Everyone had dreaded it for a long enough time, and then it burst upon the country without as much as a how-do-you-do. There had been much crying and kissing and sending off, and it seemed as if some terrible disease had swallowed every young and able bodied male in the town. They had gone off to conquer or be conquered. It was while the menfolk of Brookbrier were thus engaged, that Little Eddie made his first appearance.

If we were to ask one of the people passing us on the street about him, they would smile and sigh and shake their head and sigh again.

“He don’t rightly understand when one talks to him, ma’am,” they would say. “He just looks at a person and says in his strange way, ‘gdzie są dzieci?’”

Or if we asked the baker, he would say,

“The way that young’un is always a’gazin up at the sky, makes a body think he shoulda been a bird, and I tell the truth I do, ma’am. But I give the lad a piece of bread when I can, that I do.”

But if we were to ask old Mr. Beekly, the lamplighter, he would look very wise and say thickly, “He’s a good deal too contemplative for a grownup, and very much too innocent for a child.” What sense this makes, I haven’t the foggiest.

For the first two weeks of his short stay, Eddie could be found a few feet from his tree, flat on his back, looking up at the clouds and humming. He could always get a bit of bread from the kindly baker, and he got his water from the trickle that divided the town square in half.

Little Eddie carried a small wooden pipe, and every morning and afternoon for about an hour you could hear him blowing on it. During these daily recitals, all the children would come to sit under the Backwards Tree and listen, sitting cross legged on the grass with flowers in their hair. They made a most attentive audience, but Eddie never spoke to them. He only smiled at them, his eyes looking sad and hopeful. Mr. Beekly declared that Eddie’s tunes gave him a shiver of something cold up his spine. The notes themselves seemed haunting and lonely, like they were searching for something they would never find.

It was during Eddie’s third week of being a Brookbrier resident that the bombs fell. For a solid six days the planes seemed to decorate the sky as frequently as the clouds Eddie loved to watch. The little trickle through the town became brown and swollen with debris. In the evening, the sun struck the water in such a way that it turned a dark red. Eddie didn’t drink from it any more.

There came a day when the sky was free from planes. It was a welcome reprieve from the constant din and commotion. Eddie sat under his tree, which had survived the barrage somehow, and fingered his pipe. None of the villagers knew where he had gone when the bombing started, but here he was, blowing on his flute. The children all came out from the shelters, not heeding their mothers’ anxious cries and calls. As Eddie played, he saw their faces; white, tear stained, and terrified. His pipe faltered and he switched his melody. It beckoned to the children, and they all understood.

That night the planes returned, and Eddie’s Tree, the only one standing, fell. Finally, the last rumble of the last bomb died away, and as the mothers and grandmothers sunk into an exhausted slumber, Eddie’s new melody could be heard in the thick smokey darkness. The children peeped out from their hiding places and saw that the tree was gone, but that Eddie now stood where it had been.

It was November 17th, 1939, and the sound of boots on the cobblestones shook the shattered walls and rooftops of the village. But the boots did not belong to the victorious fathers and brothers of the waiting mothers and sisters. They belonged to strangers with steely eyes and firm, cruel mouths. As the women crowded to the windows to watch in tears and horror as the soldiers marched by, they whispered hoarsely for their children.

“Bobby! Quick! Come and and stay by me. No going out today!”

“Anna, you’re not to move from the shelter. Stay there, my dear.”

But none of the children answered. Nothing but silence. Not a sniffle or a sob. The poor mothers went wild with confusion. Through the ruined streets they ran, calling for their little ones, digging beneath heaps of fallen stones and rubble. They threw themselves down at the feet of the stone-faced men, imploring them to release their daughters and sons. But the intruders only stared at them as if they’d lost their wits, or laughed and kicked dirt in their faces. Children? They hadn’t seen any children. They were probably hiding under their beds, the worthless little brats.

A week of intense mourning came and went.

And then a letter arrived for the baker’s wife. A relative from a village in Poland had sent the letter a full month before and it had just made its way through the war torn country to Brookbrier. It began this way.

“My dear sister,

I must make this brief as I’ve only a scrap on which to write. There’s a strange boy, a wanderer from one of the first places to be invaded in our country. He carries a pipe. The bombs took everyone in his village but him it seems. People say that ever since his home was destroyed he has been searching from town to town for the children the bombs took. Be cautious of him. His strange tunes seem to beckon little ones and they follow him. They say he believes that all young ones are lost and wandering as he is, and he’s taking them back to their home, to safety, to the old Poland, to his village. He just came through our quiet town before it was taken and now my two little boys are gone. We heard the news of him just too late.”

Love,

Hannah Jo <3

Leave a Reply